Meatballs – they seem so simple, yet let’s be honest – how many times have you tasted or made something that, when you bit into it, just didn’t quite cut it? Me too. No worries though – like all good things, there are keys to consistently exceptional meatballs, and if we know and follow the rules, we’ll churn out delightful little balls of deliciousness every time.

Meatballs can be made from all kinds of proteins, from tofu to beef, pork, or poultry. Any of those options can and should turn out juicy and delicious. When they don’t, there’s almost always a broken cardinal rule or three to blame. Here, for your edification, are the most common culprits and solutions.

Dry Meatballs – Too little fat is the most common cause. Proper meatball mix fat content should be around an 80%-20% ratio of protein to fat – that’ll give you consistent results. If you’re adding cheese, sour cream, Crema, crème fraîche, chèvre, whole milk yogurt, etc, don’t forget to factor that in. As such, starting with 90%-10% protein will often do the trick.

Overcooking – this happens most often because we disregard internal temperature when we’re cooking meatballs. You should pull ‘em when they hit 160° to 165° F – They’ll easily hit ten degrees higher than that after you yank ‘em, so don’t go any higher in the oven.

Keep overcooking in mind when you reheat/cook them further in sauce – yes, braising keeps things from drying out, but if you’ve baked to proper temp, the sauce session should be monitored for heat and time – it’s still possible to overcook meatballs in sauce – it happens a lot.

Overworking – this occurs most often due to mechanical interference, AKA mixing with something other than your hands. When meatball mix is ready to form and bake, it has a feel – firm, not too wet or dry, and slightly springy. You can see all your ingredients, and know that they’re well mixed – you can’t get there unless you work it by hand – do that, and you’ll feel, smell, and see when your mix is ready to go.

Wet/Loose Meatballs – Believe it or not, this happens most often due to improper ratio of breadcrumbs/bread to meat. Yes, breadcrumbs hold moisture and are vital to the proper texture of meatballs, but add too much and you overpower your binder and end up with soggy or weak meatballs. If you really go overboard on crumbs, you’ll produce something with the texture of a matzo ball, and that’s not so good. 1/2 cup of crumbs or one slice of bread per pound of protein is the sweet spot.

Egg Problems can also lead to loose meatballs. You may think eggs are adding moisture to the mix, but that’s not their job – they’re there as a binder, and they’re critical to firm, bouncy meatballs that hold their shape. Add too much egg and you get soggy or sloppy – add too little and your balls fall apart. A ratio of one medium egg per pound of protein is the rule of thumb – if you add significant quantities of uncooked veggies to your mix, another egg is warranted.

Boring meatballs – Don’t laugh, it happens a lot. I think that folks get a mindset along the lines of ‘I don’t need to season and add herbs to my meatballs, because I’ll have all that in the sauce.’ Let’s do a quick experiment to test that theory – take a bunch of rubber balls, and cook them in your best pasta sauce… But seriously folks, the insides of a meatball have to be as great or greater than whatever they’re served on or in. Add veggies, cheese, herbs, spices, including salt and pepper in your mix, period, end of story.

Size matters – when you’re ready to form, use a disher or an ice cream scoop if you’ve got one. If not and you’re rolling your own, thoroughly clean and dry your paws, then oil them lightly – that’ll keep the mix from stickin’ to ya. In essence, size should based on what you plan to do with ‘em – if you’re not sure/gonna do different things, a 2 oz. ball should work great. If it’s something like Italian wedding soup, 1 oz. is better. If it’s something where you really want them to stand out, and will serve maybe 2 or 3 per person, a 3 oz. ball is fine.

Enough about problems – let’s flesh out ratios, so we can build our own recipes with whatever we want.

Cheese – You can use dang near anything you like, but consider properties when you do – A cheese that melts really well will want to leak out of meatballs – harder cheeses, not so much. 1/4 to 1/2 cup per pound of protein is the sweet spot. If you use something really soft like ricotta or chèvre, you may want to deploy that second egg in order to keep everything tight.

Veggies – you can add up to 1 cup per pound of protein with few worries, but there are caveats – if you’re adding something really wet like fresh tomato, consider gutting them prior to deployment. Onions, shallot, garlic, fennel, carrot, and celery will all be fine, just make sure to prep them to a fairly uniform fine dice and watch the ratios – too much of a good thing will overpower your binder and lead to loose or soggy meatballs.

Herbs – fresh or dried is fine. I like to plan on a ratio of about 1 1/2 to 2 tablespoons of herbs per pound of protein – again, boring sucks, so make ‘em speak. I’ll generally go heavier on dominant notes and lighter on minors.

Seasoning – Salt and pepper are musts, period. A teaspoon of salt per pound of protein is about right, but don’t forget to factor in other ingredients – for instance, the feta I used in the recipe below is brined, so it’s definitely gonna add some salt to the mix, and hard cheese like Parmigiano and Pecorino carry a pretty good salt load too, so adjust accordingly. A teaspoon of pepper per pound of protein is about right for most tastes.

Liquids – Keep citrus juice, etc olive oil, to a teaspoon or two each and you’ll be fine. The liquid dairy stuff, if full fat, can be treated like cheese, but again, keep an eye on your binder ratio if you use them.

Enough about that, let’s make something. I told M I wanted to make turkey meatballs – her response was perfect – ‘why?!’ Ground turkey is not a fave for a lot of folks – I’ve heard it described as dry, tasteless, and downright gross. That’s exactly the challenge I was looking for to work up a perfect meatball. When I told her I was thinking about feta, fennel, and sage as major notes she allowed, ‘that might not be too bad.’ So off I went.

Ground Turkey isn’t gross, and done right, it’s neither dry nor tasteless. It can easily be found or ground in the 10% to 15% fat range, and as long as it’s fresh, it’ll have a great texture as well, but it does not pack a whole ton of flavor. As such, I was loosely thinking of Keftedes, the signature Greek meatball – something with some serious zing to it. What I took from that was dominant notes of garlic and lemon, with a robust herb punch. Try these in your kitchen just as I detail below, then make them yours. If you wanted to go further down the Greek theme, you could add curly leaf parsley, mint, cumin, or warm spices like cinnamon and nutmeg.

Urban’s Perfect Turkey, Feta & Fennel Meatballs

1 Pound 90%-10% Ground Turkey

1/2 Cup Feta Cheese

1/2 Cup Onion

1/2 Cup Fennel Bulb

1 slice Sourdough Bread

3 fat cloves Garlic

2 medium fresh Eggs

Zest & Juice of 1/2 Lemon

1 Tablespoon Greek Olive Oil

3-4 fresh leaves Sage (or 1 teaspoon dried)

2 teaspoons dried Greek Oregano

1 teaspoon fine Kosher Salt

1 teaspoon ground Black Pepper

Set an oven rack in your upper middle slot and preheat to 400° F.

End trim, peel and slice onion roughly 1/8” thick – fine dice 1 cup and toss into a large mixing bowl.

End trim, smash and peel the garlic, then mince and add to the onion.

End trim, thinly slice, then mince the fennel.

Chiffenade, then mince the sage leaves, if using.

Zest and juice the 1/2 lemon – reserve both for now.

In a small mixing bowl, vigorously beat the eggs.

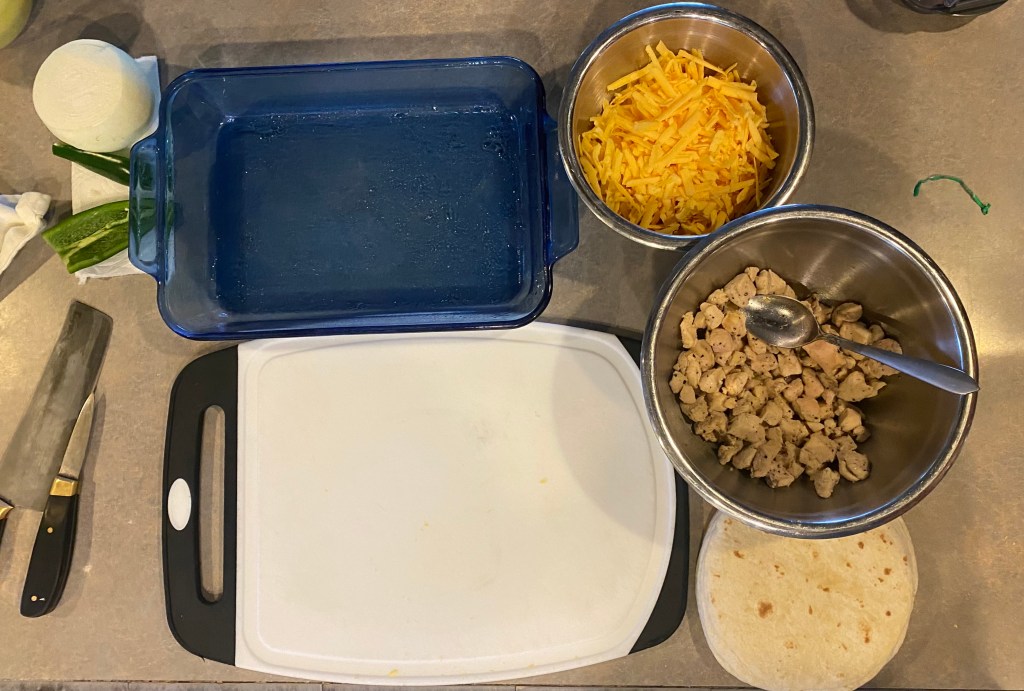

Portion feta, and olive oil.

Portion and combine oregano, salt, and pepper.

Toast the bread until lightly browned. Transfer to a shallow bowl and cover with warm water.

Let soak for about 5 minutes, then pour off the water and squeeze the bread dry. Crumble that into the mixing bowl. NOTE: You can sub 1/2 cup of plain bread crumbs if you prefer.

Add turkey, and all remaining ingredients. Mix well by hand to thoroughly incorporate, but don’t smash and mash – a firm but gentle massage is what you’re after.

Line a rimmed baking sheet with parchment.

Use a 2 oz. disher, scoop, or 2 tablespoon measuring spoon to portion and form meatballs – place them on the lined baking sheet with a bit of space between each.

Bake at 400° F for about 20 minutes, then check internal temperature – you’re looking for 165° F.

Set oven to broil, move baking sheet to upper rack and broil for 2-3 minutes until lightly browned. You can roll ‘em over and do the other side, or call it good as you see fit.

Serve with lemony Greek potatoes, rice, orzo, or other pasta, a salad loaded with tomato, peppers, and onion, and fresh Tzatziki!

For the record, the mark of an exceptional meatball – not good, not great, but exceptional – is how good they taste for brunch two days later. For the record, M declared these the best meatballs she’s ever had – and she ain’t easy.