Easy answer; almost everything.

No, really; why do y’all think that salted caramel, chocolate and a hundred other deserts are hot right now?

One of my favorite authors, Mark Kurlanski, wrote a great book all about salt. Think that’d be a boring read? Think again, it’s a page turner. Salt has been used for money as well as for food, ya know…

So, naturally, the next logical question is, “I thought salt was bad for us?”

Answer: All things in moderation, Grasshopper!

We’ve been told that line, but is it true? Turns out the answer is, probably not.

The whole sodium leads to high blood pressure thing has never really been proven. Again, moderation is the key; high sodium diets aren’t any good for you, but neither is much of anything else, when taken out of balance.

Besides that, there are bunches of good things salt does for us, including;

Aids blood sugar control by improving insulin sensitivity.

Helps maintain the proper stomach pH.

Helps lower adrenaline spikes.

Aids sleep quality.

Helps maintain proper metabolism.

Supports proper thyroid function.

Look any of those claims up; there’re ample sources of support for them.

More to the point for our purposes here, salt makes food taste good. You might be shocked at how much salt is used in a professional kitchen. They don’t go crazy, mind you, but they sure do salt, and the primary reason is that proper salting makes food more enjoyable, and specifically, it enhances quality over quantity. In that light, you could argue that proper salting helps encourage weight management, too.

Next, you ask, “OK, let’s say I buy that, why is it so.”

Ahh, I nod sagely, it’s science time! (And if you enjoy this side of food study, you’ll want to look up Harold McGee)

Chemically speaking, table salt, is sodium (Na+) and chloride (Cl-).

Why do humans dig it so? Well, we came from it, in a very real sense; The Earth is made up of lots of minerals that get continuously washed into the sea, and sea water is, therefore, salty. Sea critters get raised in that, and they are from whence we came, si? As land-based critters who evolved from sea-based critters, we still rely on water and salt for many of our basic biological processes, as described in the last paragraph. Salt plays a crucial role in allowing water to diffuse throughout our bodies properly, and as such, being relatively intelligent, we’ve developed taste buds that dig what we need to survive. Neat, huh?

Now, taste wise, research suggests that salt has the effect of flavor suppression for what we perceive as bitter tastes. By doing that, it’s thought that salt thereby allows us a greater perception of sweet and sour. It’s not really clear why it is that salt lets us taste the caramel or a green bean more distinctly; there’s supposition that the presence of the salt suppresses water within the chemistry of the food, and thereby allows volatile aromatics to become more noticeable to us. As to whether or not salt actually does something like that, or just gets our brains to perceive it as such, your guess as good as mine; that might just be a dandy PhD subject.

“Alright,” you concede, “I’m in; so how do I do this right?”

Well, first off, use the right salt. For cooking, there’s a couple things to consider, source and grain size. For my mind, sea and kosher salts are best and anything that says ‘Iodized’ or ‘Table Salt’ I avoid like the plague. As for grain size, keep in mind that the larger they get, the slower the salt dissolves. If you’re doing rubs, big grains are fine, because that nice slow, time-released salting goes great with that process. If you’re making brine, you’d like the salt to dissolve pretty quickly, so smaller is better. And keep in mind that the same thing will happen on tongues as well.

Getting the idea that you might want more than one kind of salt in your pantry? I just went and looked at ours; we have 9 varieties of sea, kosher and various finishing salts. The latter has become popular lately, and they are, in fact, pretty cool. If you’re gonna finish a dish or garnish a hand made chocolate, why not Hawaiian black, Chilean pink, or Fleur de Sel? If you’ve never tried fish quick cooked on a heated block of Himalayan Pink Salt, you aughta; it’s not only cool, it’s seriously delicious.

We use kosher and sea salts as our primary cooking varieties, flaked for canning, pickling and brining, and the various others for special touches here and there. Once you get one you like, stick to it. All salts do not weigh the same, so for baking, brining, or any other recipe where the ratio really matters, you’ll want to know where yours hits the scales. The other great thing about kosher is it’s uniformity; you can grab it and send it to a dish with great control and repeatable uniformity, and that’s important.

So, how to use the stuff like a pro?

First and foremost, the rule is, do it, but don’t overdo it. You want to taste the food better, not the salt. The best way to achieve this goal is to salt throughout the cooking process, and taste what you’re making at every step. If what you’re adding is already salty, (bacon, olives, capers, etc), taste before you salt.

Do keep in mind that salt levels will change as your dish develops. If you reduce a liquid that’s salty, it’s gonna taste saltier. Ditto for stuff you make and then shove in the fridge for a spell. On the too light side, dairy sucks up salt like nobody’s business, so multiple checks are warranted with, say, a cream soup or stew.

Do it like this and your dishes will properly develop flavor as they cook, with the added fringe benefit that, if you screw up and hit it too hard at an intermediary step, you have time to fix it.

OK, so if you do screw up and over salt, whataya do? Adding cream and or butter, as mentioned above, reduces saltiness, so do that if your dish warrants it. Starch can do the same thing, so a piece or two of bread, soaked in milk for about 10 minutes, squeezed dry and added to the dish can help; note it also acts as a bit of a thickener though. The great Julia Child advocated grating a raw potato or two into a dish, allowing it to simmer for about 10 minutes, and then straining them out, noting that, “they’ll have absorbed quite a bit of the excess salt.” Anything good enough for Julia is certainly good enough for us, right?

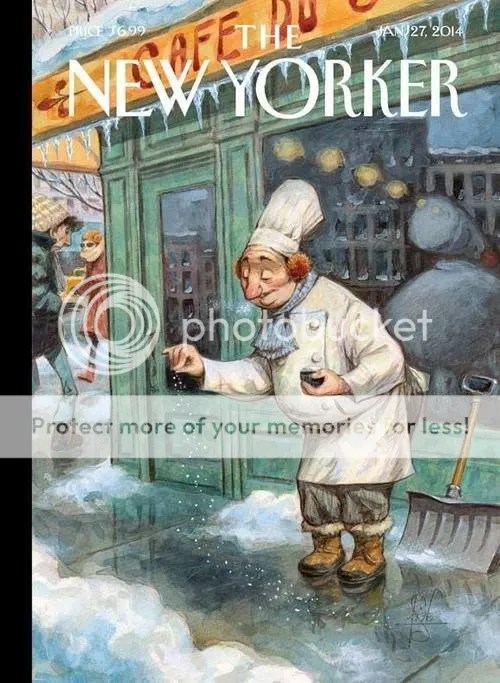

Now, one last tip, helped by this New Yorker cover; I know y’all have watched Food Porn TV and seen a bunch of chefs do this: get a nice pinch of that kosher salt, and raise your hand about a foot above the pan or bowl, and ever so slowly, release a dusting of salt from that lofty height. You didn’t really think those chefs do that just to look cool, did you? The increased drop height will allow you to better judge the amount of salt you’re adding, as well as allowing the salt granules to spread more evenly over the food.

Oh, and you’ll look cool when you do it, too.